The tradition in my classroom for the last day of school is simultaneously one of the best things I do and one of the hardest. I have the students of every class period gather into a circle and I tell each of my 8th graders something I will always remember about them, something I will miss about them, or something I hope for their future. I do this with every class throughout the day, for every one of the 140 students who’ve been entrusted to my care and teaching for the school year. It is one of the hardest days of the year because I have to let go of all these young people. I send them off into the world hoping that they are prepared, hoping that they feel strong and successful, and hoping they know that I see them, I know them, I care about them and that it doesn’t end when they leave my classroom.

This year, the routine was no different. I circled up my classes and proceeded to publicly send each student off into the world with a compliment. I told Alex that his writing was powerful; that he should always have confidence in his voice and his unique perspective on the world and that he should keep his Precise Pilot V5 Rollerball Pen with him at all times. I told Tatiana that what I’d remember about her most this year was when she was so frustrated when trying to finish a unit final after school one day that she stormed out of the classroom in tears…and then came back to finish that final and make herself incredibly proud. I told Victor I’d miss hearing him say, “True” in that inflection that has now become part of my speech, that I’d miss our morning hellos to each other, each reciting the other’s full name (middle names included), and that I’d miss the way he infused his humor into helping run our classroom. I told Jade that I hoped she’d keep writing, that telling the story of her father’s hunger strike at the detention center was important, that she and her mother showed fierce endurance, and that her story mattered. I told Cristian that I hoped he’d keep asking for help when he needed it as he’d learned to do this year because when he took a risk and advocated for himself, he benefited. I told Julio I’d remember him getting hooked on reading this year, reading every gossipy novel he could find and not caring that he was not the typical audience for teen girl drama. I told Tyson that I knew from the narrative he’d written about his grandfather that he truly understands the value of family and that he would grow up to be a good man. I told each of them something to bolster their confidence, validate their experience, strengthen their heart.

When the last period of the day came, my final class came in. We moved to the circle together. I went through the same process, but had to stop when I arrived at the final student, Alyssa. She looked at me and said, “Can you not say anything to me right now? I can’t handle it.” I looked her in the eye, which was all the encouragement we needed to both start crying. We stood up and silently hugged each other. Class ended and other students joined the hug and then filed out of the room.

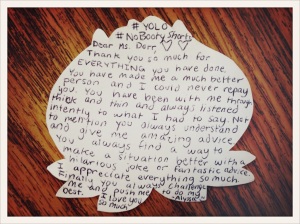

Later I found two handmade cards taped to my computer screen. One was from Alyssa. It was a card thanking me and included the line, “You made me a much better person and I could never repay you.”

Early that day, Alyssa had been honored with the Principal’s Award. Part of what was shared about her was what I’d written: “Alyssa’s enthusiasm for life exceeds most people’s. She is open and honest and incredibly excited by just about everything. Alyssa shares her talents with classmates by supporting them through great questioning, supportive comments, and positivity. In addition, she holds herself to very high standards. Alyssa pushes herself to revise her work, put in great effort, and accept feedback. She attacks things with gusto and generosity, which means she will have a rich, full life and will enhance the lives of those around her.” Unknowingly, we’d both credited each other with enriching those around us. That is the beautiful reciprocal nature of teaching. Being a teacher has made me a better person. Having the honor of impacting young people’s lives has been a humbling and powerful experience.

Cleaning up my classroom this year after students left that last day was different for two reasons. One reason is because I saw Alyssa making her way off campus. She told me that she planned to go home and be sad and eat the Oreos she had purchased the previous evening as part of her wallowing plan. I told her it sounded like a good plan and that Oreos were my favorite. Her face brightened and she asked whether it would be okay to go home and then return with the Oreos for us to eat together while she helped me to clean my classroom. Of course, I said yes.

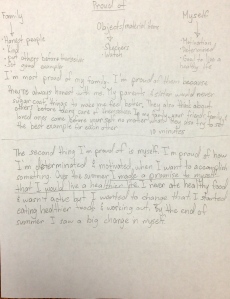

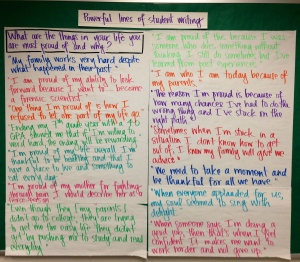

As Alyssa organized the classroom library, I read through the student surveys I’d collected the last full week of school. Each year, I seek feedback from my students about my teaching and their experience of being a student in my room. In the responses, I found the following comments:

- Without this class, I wouldn’t be ready for high school. You made me figure things out on my own and even though I didn’t always like it, I know you helped me to become independent.

- In this class, I stressed about nothing so I could focus on my studies and learn.

- Why do you teach? You teach because you’re a believer. You want to challenge us and for us to challenge ourselves and succeed. You believe education is the greatest possession anyone can have, therefore you teach.

The other reason cleaning my classroom that day was different, though I was not allowing myself to acknowledge it then, was because I would not just vacate my classroom for the summer; I wouldn’t be returning to it. Though many days are ridiculously tough and the challenges seems insurmountable and the amount of tedium and numbers of decisions to be made in a single day are mind-numbing, knowing that students are deeply impacted has kept me at it for 11 years. Education is opportunity. Education is freedom. Education is access. Education is power. Education is choice. Education is possibility.

I am so committed to ensuring that every Alex, Tatiana, Victor, Jade, Cristian, Julio, Tyson, Alyssa has exactly what they need to succeed, to be challenged and grow, and to have whatever life they choose that I am willing to step out of the classroom to drive this work at the systems level.

That day, I didn’t say goodbye to anyone. Granted, I don’t like goodbyes, but I also didn’t say that because I will remain connected to my classroom and to my students. That strong connection and commitment will continue to inspire me and focus my work.

I told Alyssa in an email a few weeks later that I would be moving into a new role. She wrote back to me, “Even though I believe you are a very wonderful and inspiring teacher, this job sounds perfect for you. You will make such a huge impact on education in this position. This makes me feel very proud to have been in your class. I’m very happy for you.”

I couldn’t have asked for a better farewell.